In honor of Black History Month we celebrate Oakland's pioneering African Americans.

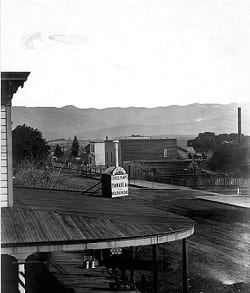

For most of us, the story of African Americans in Oakland begins with the westward migration during World War II. And while that is an amazing history, the story really began nearly 100 years before when Oakland was little more than dirt roads and clapboard buildings. The original town ran along 14th Street over to the estuary, from the tidal slough we know as Lake Merritt to West Street.

The same dreams of personal and economic freedoms that brought whites west drew African Americans to the state. They had come to California to start new lives unharnessed by tradition and restriction. They had come in search of gold. They had come accompanying slave masters. They had come to set down new roots. The first East Bay census, taken in 1852 when the city was founded, recorded that five African American men and one African American woman, and eight foreign-born African American men lived in Oakland. In those early days, African Americans in Oakland worked as sailors, laborers, draymen, barbers, maids, dressmakers, railroad porters, hotel workers, cooks, and waiters.

Once the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, with Oakland as its western terminus, the city's African American population grew steadily. The Transcontinental Railroad (the Central Pacific, later the Southern Pacific) employed African Americans as porters, maids, cooks, redcaps and waiters. Train travel became popular, and with the creation of the Pullman sleeper car, much more comfortable.

The Pullman Company hired only African American men and women to work as railroad porters and maids. They worked long, hard hours, traveling back and forth across the country, serving train passengers on an as-needed basis. Though the work was arduous, it gave these women and men an opportunity to see the country, to earn better wages than the average day laborer or domestic, and to learn about other communities. With more people coming into town jobs in the hospitality industry became more common. For example, in 1874, according to historian Beth Bagwell, twenty percent of Oakland's African Americans worked for the elegant Tubbs Hotel in nearby Brooklyn.

Though California entered the Union after long and passionate debates as a free state in 1850, one of the key political issues that concerned African Americans in the state was the issue of slavery. Subsequently another debate followed: whether any slave, by being brought into the state, would be, therefore, free. Essential to African Americans gaining equal footing in California, was winning the “right to testimony” in civil and criminal cases, equal taxation, suffrage, and settling the homestead question (the right to purchase and protect property). Personal security must have been on the minds of African Americans because, without the protective right to testify on one’s behalf, the possibility of being kidnapped into slavery was not a remote one at all. Like Native Americans and Asians, African Americans could not testify against whites in court. This inequity left any African American person particularly vulnerable to anyone claiming they were a runaway slave. These “Black laws” propelled California’s scattered African American populations into action.

In 1855, 1856, and 1857, African Americans from across the state gathered in Sacramento and Marysville for the State Conventions of Colored Citizens, to demand voting rights, educational opportunities, and other civil rights. They lobbied the state legislature and the courts to include and protect the growing African American population. Jeremiah Sanderson, a prominent educator and minister in Oakland, played a key role in the fight to desegregate California schools. (His daughter Mary became the second African American school teacher in Oakland.) It was not until 1863 that African Americans, after years of diligent lobbying and raising public awareness of their campaign that they gained the right to testimony. In that same year the Homestead question was resolved.

African American entrepreneurship also helped establish a stable community. As early as the 1850s, men like William Rich who operated a restaurant that opened in 1855 and Isaac Flood who ran a plastering business during that time helped build a durable, self-sustaining community. Grocery stores, barber shops, boarding houses, saloons, livery stables, and furniture stores were some of the businesses operated by African Americans.

By 1880, the community had grown to 593 (out of 34,555 total residents). By 1900, the African American population was 1,026 of Oakland's 66,960 residents. Though its population was small, Oakland's African American community had built a healthy network of commercial, educational and social institutions including churches, private schools, social clubs, music venues, real estate firms, insurance companies, funeral homes, and recreation centers by the end of the nineteenth century.

Add a comment to: African Americans Establish a Growing Community in Early Oakland