Posted by Dorothy Lazard on Thursday, February 15th, 2018

African Americans worked to feed, clothe, and house their seniors in early Oakland.

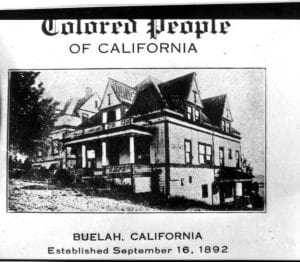

The forgotten community of Beulah was a district of large, beautiful homes, many of which provided social services to the orphaned, poor and elderly. It was located in what is now East Oakland, just north and east of Mills College. One of Beulah’s most prominent institutions at the turn of the 20th century was the Home for Aged and Infirm Colored People. Retirement homes at the time were racially segregated, accepting whites only, so Oakland’s African American civic and religious leaders came together to establish a home for its seniors and aged homeless.

The Old Peoples Home Association incorporated in 1892 for the purpose of building such a home. Its founding board included several prominent Oakland-based African American women such as Hettie Tilghman, Julia Shorey (shown here with her family), Harriet E. Smith, Ann S. Purnell, and Mary C. Washington. This early board of directors—and those who followed them—sponsored festivals, dances, and concerts to raise money to cover building costs. Land for the home was donated by a white Christian missionary, George S. Montgomery, who had settled in Beulah with his wife Carrie in 1890. Carrie Judd Montgomery called the sun-soaked, hilly setting above Mills Seminary “Beulah Heights.”

The Old Peoples Home Association incorporated in 1892 for the purpose of building such a home. Its founding board included several prominent Oakland-based African American women such as Hettie Tilghman, Julia Shorey (shown here with her family), Harriet E. Smith, Ann S. Purnell, and Mary C. Washington. This early board of directors—and those who followed them—sponsored festivals, dances, and concerts to raise money to cover building costs. Land for the home was donated by a white Christian missionary, George S. Montgomery, who had settled in Beulah with his wife Carrie in 1890. Carrie Judd Montgomery called the sun-soaked, hilly setting above Mills Seminary “Beulah Heights.”

The Home was completed and receiving “inmates” (as residents were called) in October 1897, a mere two months after the cornerstone was laid. Alvin A. Coffey, a former Kentucky-born slave who made his fortune during the California Gold Rush, was the home's first resident. This California pioneer had bought his freedom and set about to purchase the freedom of his wife and seven children. By 1860 the family was reunited in Northern California. In his later years Mr. Coffey moved to Oakland and contributed $500.00 to the Old People Home Association to help finance the home’s completion. Located at 5245 Harrison (now Underwood Avenue), it bordered the northern side of Mills. The two-story Victorian originally had sixteen rooms. By 1905, after an eight-room addition was built, the home could accommodate nineteen residents. The seniors, who were charged a $500.00 lifetime membership fee, were kept busy with tasks such as sewing, knitting and gardening. The use of alcohol and drugs were strictly prohibited and living quarters were sex-segregated.

Mr. Coffey, who was a major benefactor and supporter of the home, died there in October 1902 at the age of 80.

Money was always an issue for the Home for the Aged and Infirm Colored People. The directors of the home hosted “Donation Days” to garner much-needed funds and supplies for the maintenance of the building and services. The staff accepted not only monetary contributions, but linens, cooking utensils, supplies, volunteer labor, and food.

As California's first institution to serve African American seniors, most of whom were former slaves, the home is historically significant. Beulah, once a suburb of Oakland, was annexed to the city in 1909, along with the towns of Fruit Vale, Melrose and Elmhurst. As a result, some of the social services that once occupied the small community relocated to more central parts of Oakland while others folded due to financial constraints. The Home for Aged and Infirm Colored People remained in Beulah and closed in 1938. Mills College purchased the property on which the home sat, and shortly thereafter, in 1939, Mills administrators ordered the home razed.

The Home for Aged and Infirm Colored People is just one example of how Oakland's African Americans, through hard work, cooperation, and determination sustained their community. To learn more about the Home for Aged and Infirm Colored People, visit the Library's Oakland History Room and the African American Museum and Library at Oakland.

Add a comment to: Lifting as They Climbed: Making a Home for African American Seniors