This Bike Month, we’re thinking about Oakland’s long cycling history. Here's a look at biking in Oakland … 125 years ago.

In the last decade of the 19th Century, Oakland experienced rapid growth in land area, population, and industry. The annexations of 1891 and 1897 added over five square miles to the city, and the population grew by over a third during this decade (to almost 67,000 by 1900). People moved here in droves to work in railyards, lumber, canneries, foundries, and factories producing goods from cotton and grain. The city was bustling.

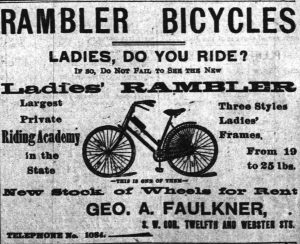

Bicycle fever hit an all-time high in the mid-1890s on a national scale. The new “safety” bicycle was everywhere – a diamond-shaped frame with two equally-sized wheels, which brings the rider much closer to the ground than the topple-prone penny-farthings of earlier years. Along with the invention of pneumatic (air-filled) tires and new brake technologies, biking became safer, more comfortable, and more affordable.

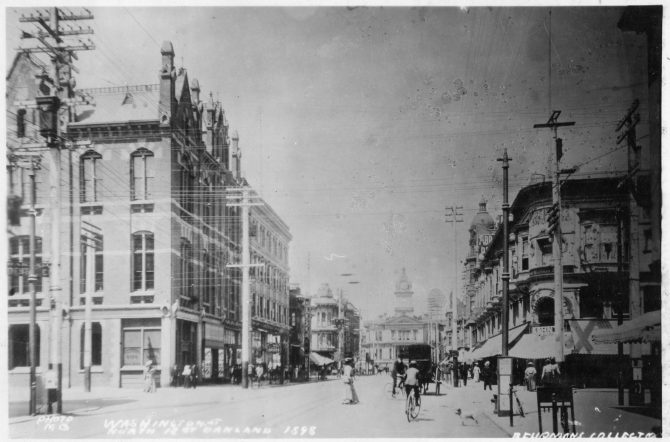

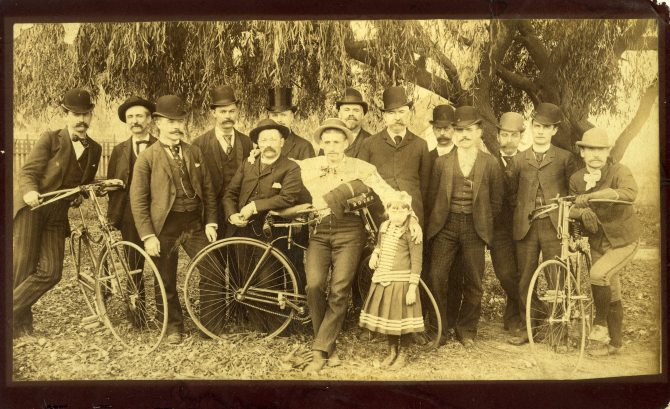

Oaklanders were swept up in the popularity of the bicycle during this time. Cycling clubs organized rides and races for recreation and sport. Cyclists traversed the city, competing for road space with pedestrians, horses, carriages and trains.

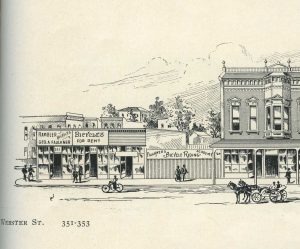

Bike shops multiplied. Christian Rode & Son operated their store at 875 Center St for several years during this time period.

Western Union started to employ bike messengers as an efficient and fast means of telegram delivery. Here's a Western Union delivery crew taking a well-deserved break at Lake Merritt. #messlife

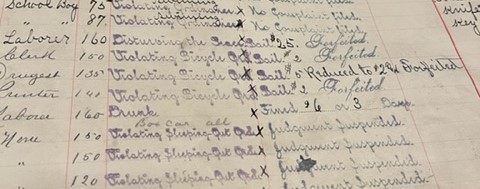

Bikes were ubiquitous and added to the traffic melee. Without designated lanes or crossings, streets were shared amongst users of many different forms of transit. Attempts were made to restrict the movement of bikes, and many arrests were made for violations of bicycle ordinances. (This often stemmed from biking on the sidewalk during certain hours.) As this city jail roster attests, this "crime" was common - they wrote this charge so many times, they decided to have a stamp made.

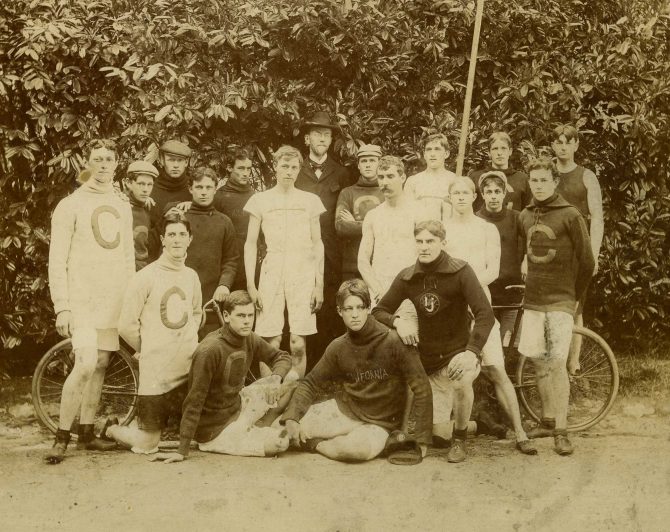

Cycling was a popular spectator sport. Velodromes and cycle tracks were built in San Francisco, San Jose, and in Emeryville's Shellmound Park. The Sports section of the Oakland Tribune announced upcoming meets, race results, gossip about star athletes, and the activities of local clubs.

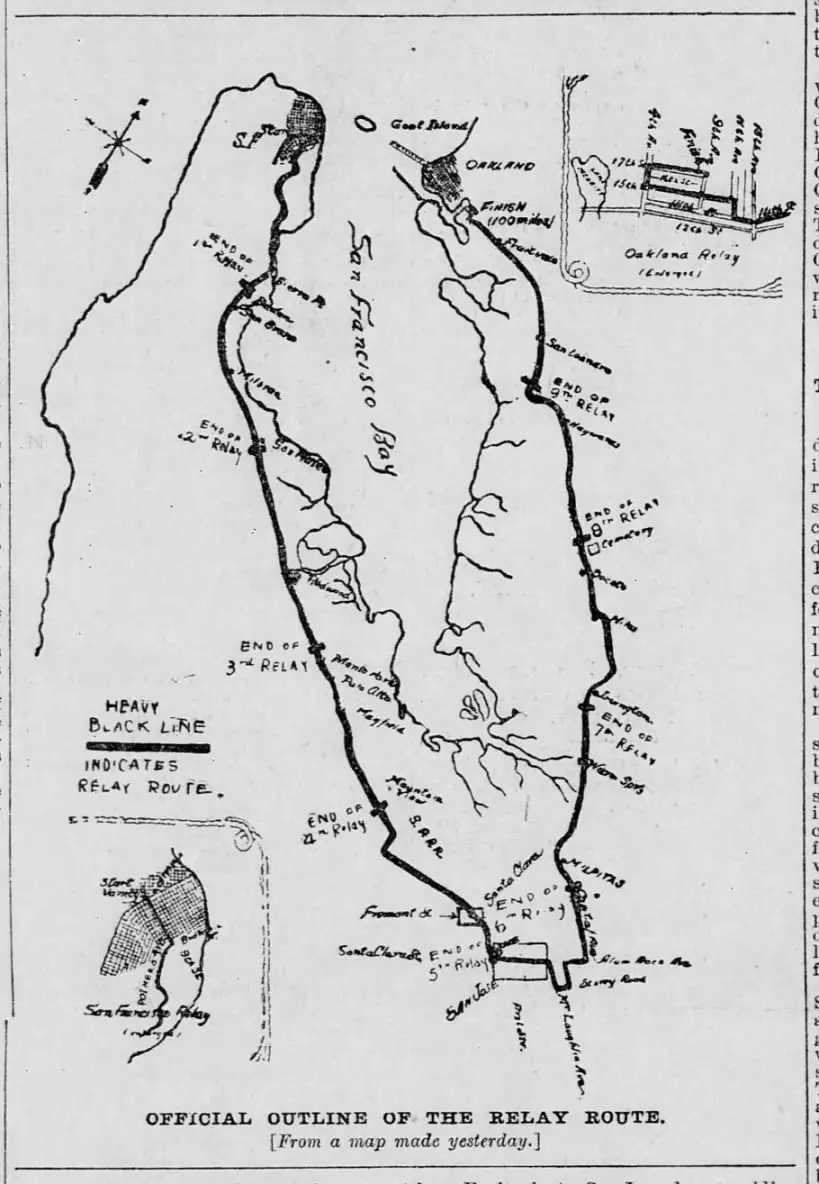

An annual SF-Oakland 100-mile road relay was held in the spring. Dozens of cycling clubs participated. The race was broken into ten sections of ten miles and involved umpires with white flags to guide riders along the course.

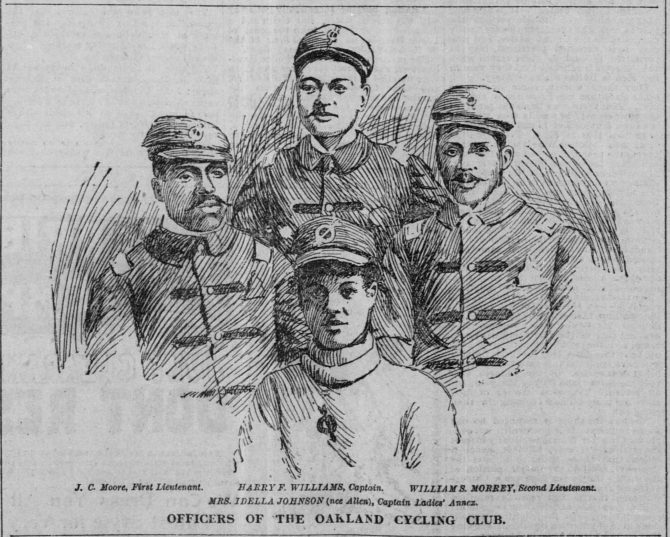

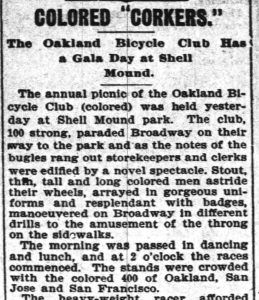

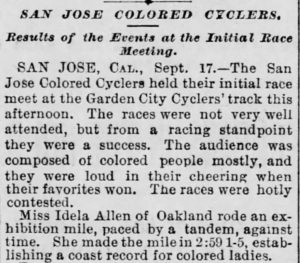

One of the more active clubs in the East Bay was the Oakland Cycling Club. The OCC was comprised entirely of Black riders. The leader of the "Ladies' Annex," Miss Idella Allen, was an active racer and set West Coast records.

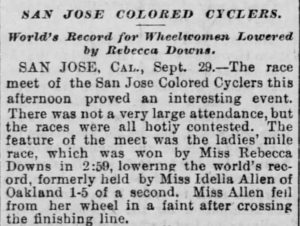

A rivalry sprang up between the Oakland Cycling Club and the San Jose Colored Cyclers. Fans could follow the back-and-forth record breaking between Idella Allen and Rebecca Downs in their paper's sports section.

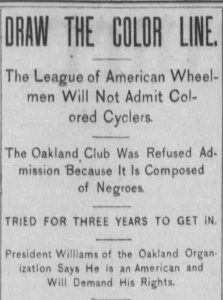

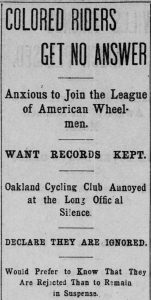

At the time, the League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W.) wielded incredible power over competitions, records, and racing rules. After the L.A.W. instituted a color line in 1894, the Oakland Cycling Club found themselves in a years-long battle for membership and recognition. OCC President Harry Williams told the San Francisco Examiner, "It is simply preposterous that we, who are Americans, cannot become members of this organization just because of our color. It's a shame and an outrage. It would have been just as sensible for them to have told all the red-headed men who ride wheels that they would have to form a red-headed League of American Wheelmen. [...] What am I going to do? Why, fight this thing until we get recognition" (SF Examiner, July 21 1896, p. 10).

Although OCC riders broke records and made a striking impression on the cycling scene in the Bay Area, their results were never sanctioned. L.A.W. instituted their color line in 1894; it wasn't until 1999 that they officially revoked the resolution. Tragically, the achievements of the Oakland Cycling Club were not recorded in the annals of cycling history, but we can still learn their story through the newspaper record. (For a fascinating perspective of the early days of bike racing, check out the autobiography of Major Taylor, the first Black world cycling champion.)

Add a comment to: The Bike Craze of the 1890s in Oakland