Most school-age students know that if it weren't for non-violent protests such as sit-ins, they wouldn't be able to share a restaurant or lunch counter with their friends regardless of skin color. They also understand if it weren't for the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s - 1960s, everyone wouldn't be able to ride the bus equally or even attend integrated schools. Although most children learn about the Civil Rights movement, they rarely learn about public library sit-ins. So I am going to give you a brief history of some of the people who fought to desegregate American Public Libraries:

On August 21, 1939, five well-dressed Black men entered the Alexandria Public Library in Alexandria, Virginia. They politely asked the librarian to register for library cards and were denied. After being denied library cards, they selected books from the shelves, sat down at separate tables, and began to read quietly. The librarian called the police to have the men removed from the library.

The coordinator of this protest was Samuel Wilbert Tucker. He was also a lawyer for the state of Virginia. That day, Mr. Tucker was not at the library and called the local newspapers to alert them of the protest. Over 300 spectators and newspaper photographers watched as the men were arrested by police, removed from the library, and charged with disorderly conduct. Mr. Tucker defended the men in court, and the judge refused to rule on the case.

The judge refused to rule on the case because this was a complicated situation. Although the Black men reading in the "whites only" library was a direct violation of the library's "whites only" policy, there was not a "colored library" available in Alexandria for the men to use. The lack of a "colored library" was a direct violation of Virginia state law. Although segregation was legal in 1939, it was illegal to deny "equal" resources for white and colored citizens. So technically, without a "colored" library, the men were legally allowed to use the "whites only" library. At least, that was what Mr. Tucker argued in court.

Because integration was not an acceptable solution in the Winn-Dixie south in 1939, the library board quickly approved the construction of a "colored" library which opened in April 1940. Most books, furniture, and fixtures in the new "colored" library were donated used books or castoffs from the main Alexandria library. When invited to apply for a library card at the "colored" library, Mr. Tucker refused. He argued he deserved equal access to the main library. The Alexandria Main Library was finally desegrated for adults in 1959. In 1962 the library was finally fully desegrated, permitting Black children to use the facilities.

In 2019, research by Alexandria Library staff discovered that the charges against the five men were still outstanding because although the judge never issued a ruling, the charges were never dropped. In October 2019, the Alexandria Circuit Court dismissed all charges, ruling that the men were "lawfully exercising their constitutional rights to free assembly, speech and to petition the government to alter the established policy of sanctioned segregation at the time of their arrest" and no charges should have been filed.

The Alexandria sit-in was the first staged sit-in to protest against library segregation. It happened 15 years before the birth of the 1954 Civil Rights Movement. The names of these pioneering men are William Evans, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, Clarence Strange, and Otto L. Tucker (Samuel Tucker's Brother).

On March 1, 1960, twenty Black high school students entered the "whites-only" library branch of the Greenville Public Library in Greensville South Carolina. Library staff closed the library for the day to avoid the disruption this sit-in would cause. Two weeks later, seven students returned to the "white's only" library requesting to use its resources. They were arrested for disorderly conduct, and later the charges were dismissed.

On July 16, 1960, eight Black students were arrested in Greensville, South Carolina, for reading in the "white's only" library. The students explained they needed to complete a homework assignment that required visiting this location, and the books they needed were not available at the "colored" library. Instead of helping them, the librarian insisted the students go to the colored branch and demanded they leave. The students did not leave; instead, they sat quietly reading until they were arrested by law enforcement. This protest was made known to all media outlets.

The lawyers for the NAACP filed a federal lawsuit, against the Greenville City Council, over the issue of segregated libraries. The Greenville City Council responded by immediately voting to close the "white" and "colored" library locations. The trial wasn't until September. The libraries were still closed on the day of the trial, so the judge dismissed the case. The judge's opinion was because there were no libraries open, if they were segregated or not is irrelevant. Although technically, this verdict was a win for the city, it upset the entire community. Since July, everyone lost library access.

Under pressure from the community, the city council quietly reopened the libraries to all the public on September 19, 1960. When the mayor was questioned by the media of the reopened libraries were integrated, he stated, "The city libraries will be operated for the benefit of any citizen having a legitimate need for the libraries and their facilities. They will not be used for demonstrations, purposeless assembly, or propaganda purposes."

This statement confirmed that Greenville's Public Libraries were officially desegregated. Although other libraries in South Carolina quietly integrated before these events, Greenville's libraries were the first in the state to be integrated as a result of public demonstrations.

The students who participated in the final protest are forever known as the Greenville Eight, and their names are: Reverend Jesse Jackson, Dorris Wright, Hattie Smith Wright, Elaine Means, Willie Joe Wright, Benjamin Downs, Margaree Seawright Crosby, and Joan Mattison Daniel.

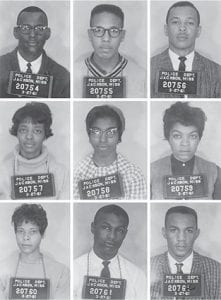

On March 27, 1961, nine Black college students from Tougaloo University, opens a new window attempted to use the Main Library in Jackson, Mississippi. Again, this was a "white's only" library, and when the students were denied access to the materials, they staged a sit-in and were eventually arrested. Their arrest and conviction led to a class-action lawsuit filed by the NAACP the following year. In May 1962, the federal courts ordered the Jackson Public Library to desegregate. These college students are forever known as the Tougaloo Nine, and their names are Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Lassiter, Alfred Cook, Ethel Sawyer, Geraldine Edwards Hollis, Evelyn Pierce, Janice Jackson, James "Sammy" Bradford and Meredith C. Anding Jr.

These are just a few unsung heroes who helped integrate American Public Libraries and fought for equal access for all. There are many more I could list, but this blog is getting a bit too long. Understand many libraries removed their segregation policies quietly and without incident. Yet, in other places, the ability to freely use any library you chose regardless of skin color was a hard-won battle. So the next time you enter the library, filled with all nations, kindreds, and tounges, give these unsung heroes a silent thank you.

Add a comment to: Unsung Heroes that Helped Desegregate Public Libraries