If you've visited the Oakland History Center you've probably noticed that we have a huge number of filing cabinets in the center of our space. Inside these cabinets you’ll find one of our most frequently-used and most valuable resources: the vertical files, aka the clipping files. These files are a great starting place for researchers because they contain articles from a wide variety of sources, newsletters, reports, brochures, and all sorts of other materials. We have folders, organized by topic, covering all aspects of Oakland and East Bay history, life, and culture, and a card index to point you to the relevant folder. We’re still updating these files, too, so you might occasionally find articles from 2022 in the same folder as articles from 1922.

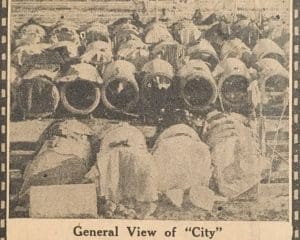

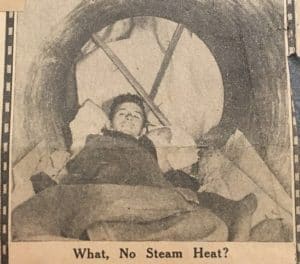

The vertical file folder for Pipe City recently caught my eye, because although I knew about Pipe City I’d never researched it in any detail. Pipe City was a famous “Hooverville” in Oakland that lasted from September 1932 until April 1933. Up to 200 men took temporary shelter in large surplus concrete pipes in an agreement with the owner of the pipes, the American Concrete Pipe Company, at the foot of Nineteenth Avenue.

|

|

|

|

|

|

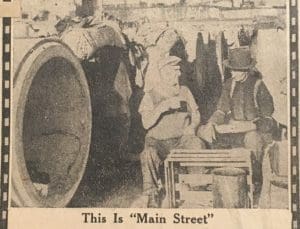

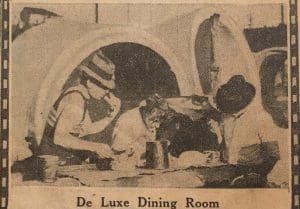

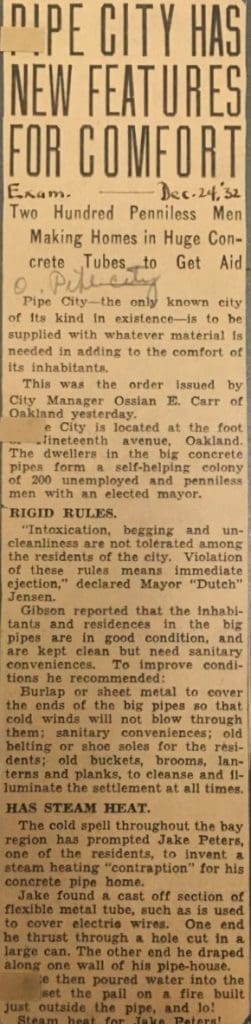

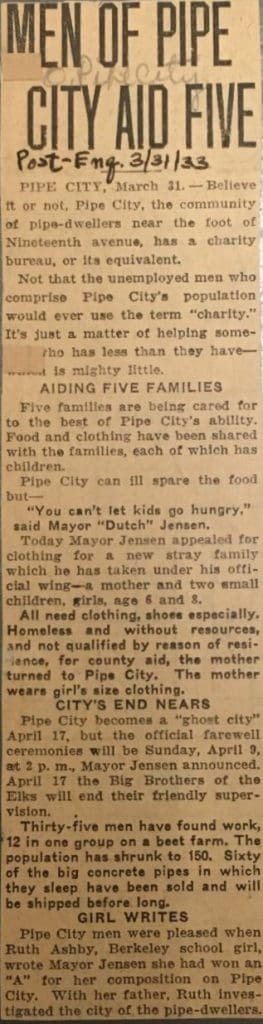

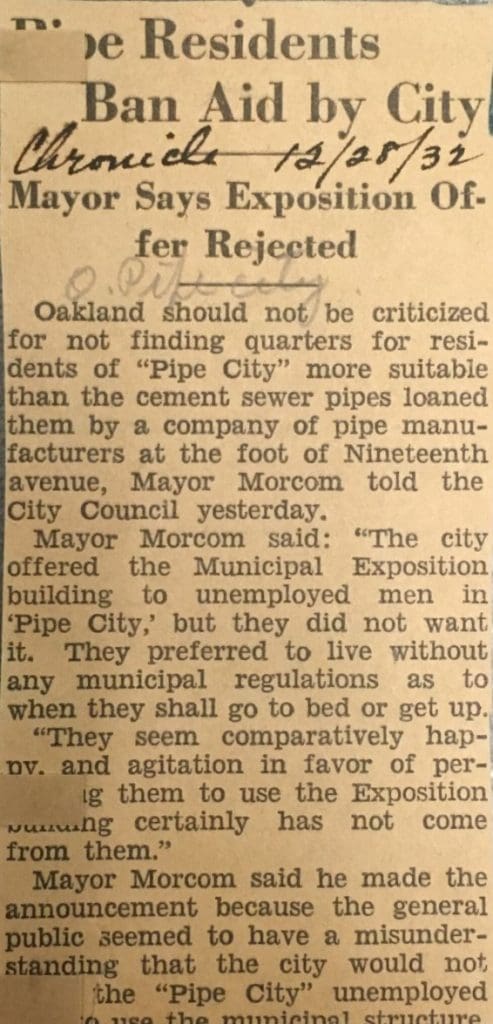

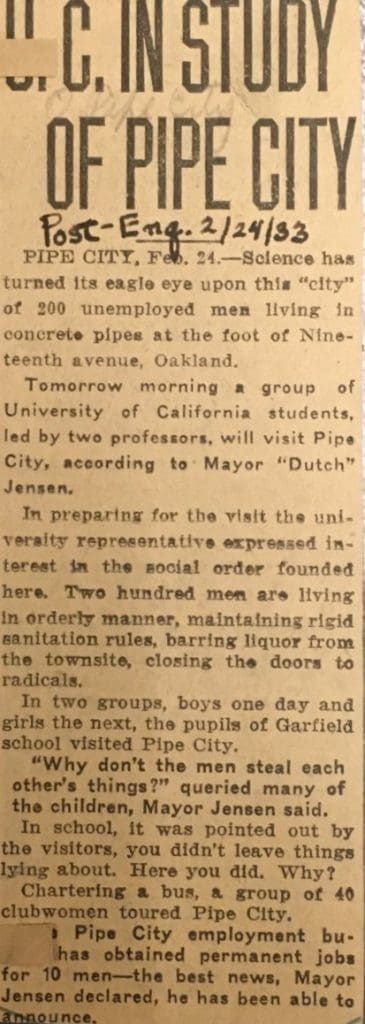

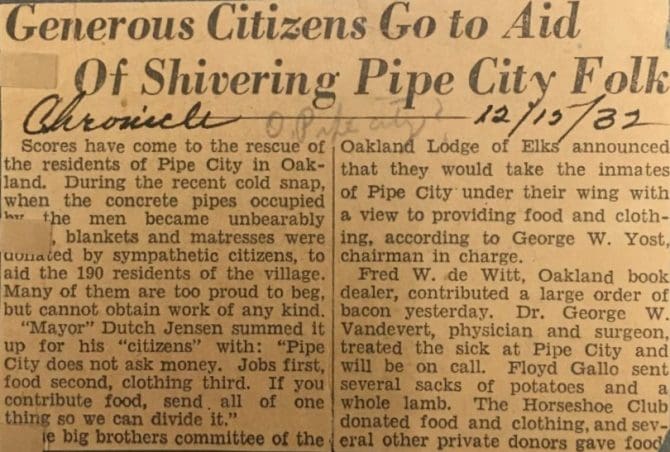

Pipe City was well covered in the media. People were interested in this unusual settlement and newspapers responded with frequent coverage, much of which can be found in our vertical file folder. Pipe City seems to have been treated as an interesting novelty by the press and the public alike, with multiple glowing articles and photo features about the residents' self-governance, their self-reliance, and their charity to others. The articles didn’t always gloss over the hardship, but their overall tone seemed hopeful. Writers were impressed by the resourcefulness of people who were able to make shelter out of abandoned concrete, and who were able to figure out how to take care of themselves when there were very few opportunities available.

|

|

|

|

|

The idea of a Hooverville – a group of temporary shelters - doesn't sound too different from what we would call a "homeless encampment" today. But despite the similarities, news coverage of people experiencing homelessness in Oakland today seems very different from the coverage of the goings on at Pipe City. Today's articles question and theorize about why people become homeless. There are stories of encampments being “cleared” and residents with nowhere to go. Government leaders are either accused of focusing too much funding and attention on homelessness or are accused of doing too little to help. The tone of today’s press coverage about homelessness is generally not hopeful, and it’s generally not focused on what homeless people are doing to make their communities work as best they can. Homelessness is portrayed as an almost insurmountable problem with no total solution in sight.

At the height of the Great Depression as many as 1 in 4 adults were unemployed, leading to a huge and sudden spike in people experiencing homelessness. Hundreds of Hoovervilles sprang up around the country, and some estimates put the total number of individuals experiencing homelessness at this time at 2 million nationwide. There had been people without adequate shelter throughout American history, with the first notable increases after the Civil War, but the Great Depression was the first time Americans saw homelessness on such a large scale. 200 homeless people living in community together on borrowed land seemed like a novelty in 1932 because it was a novelty. Pipe City wasn’t like anything that Oakland had ever seen before.

Surplus concrete pipes were no one’s idea of an ideal shelter. The men who lived there called it "Miseryville" and struggled to survive. It was the newspaper writers who thought of the catchier “Pipe City” name. The papers also focused on Dutch Jensen, the elected Mayor of Pipe City. Jensen negotiated squatters' rights with the company, organized the residents to collect food for a nightly communal "mulligan" stew, created an "employment bureau" to help residents find work, and gave frequent interviews. The main goals of the community were to provide a safe shelter, find food, and find jobs. But they also hosted visits from Oakland's Mayor and other city officials, from elementary school groups, and UC Berkeley scholars studying the "social order" of their community.

|

|

|

|

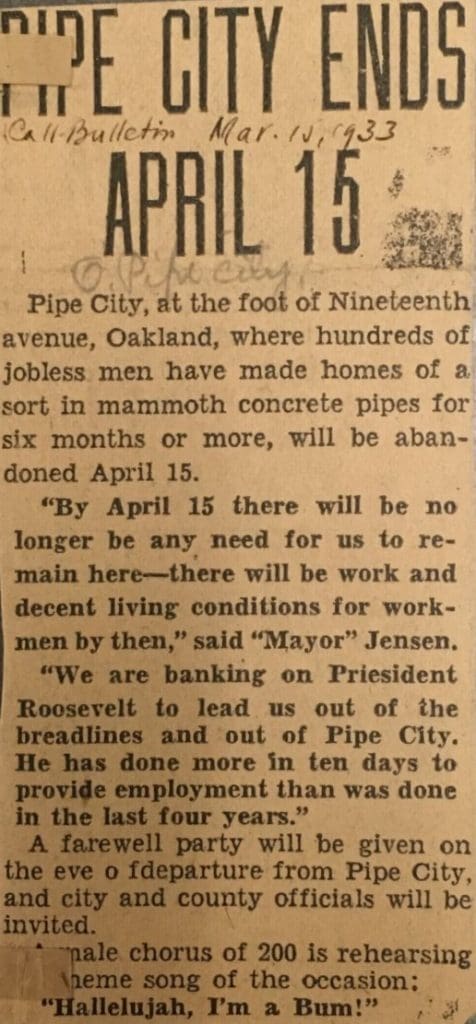

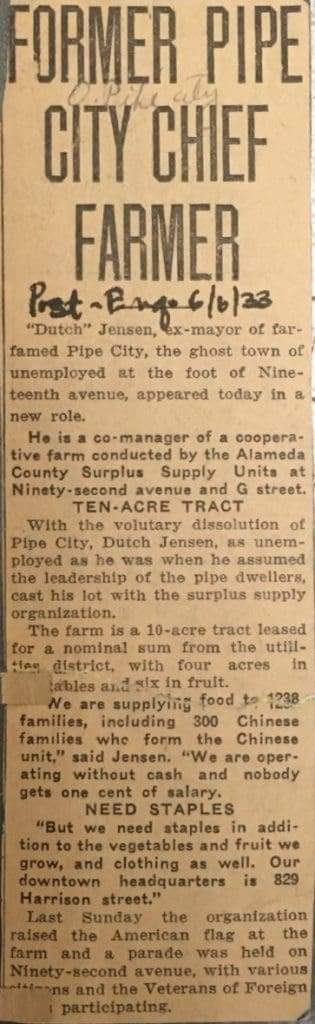

Eventually the company found a buyer for their pipes, and the residents agreed to move out, acknowledging that their situation there had always been temporary. The residents went their own ways, with many still looking for work, but reportedly hopeful that President Roosevelt's new policies would help them find jobs and eventually homes. Dutch Jensen was able to continue helping others find food and shelter while working on an East Oakland cooperative farm that supplied food to over 1000 families. Later, he worked with the East of the Lake Unemployed Club, collecting food, clothing, and furniture for 85 families.

|

|

|

And then, what happened? Unfortunately there’s no way for us to track most of the people who lived in Pipe City to find out what became of them or whether they ended up with the jobs and homes they hoped for. I'd argue that the romanticized version of Pipe City presented by the press was more or less cemented in the public imagination. It inspired Upton Sinclair’s 1936 novel Co-Op : A Novel of Living Together, which presented a community called Pipe City as a model of cooperativism. And there's a replica of a Pipe City pipe in the Oakland Museum's History section, available for visitors to climb into to imagine themselves as one of Pipe City's residents. Some other questions we can't exactly answer: was the version of Pipe City presented by the newspapers anywhere near the reality? How did this early example of a functional community that "refused aid" contribute to the idea that homeless people should be able to fend for themselves, or pull themselves up by their bootstraps?

Homelessness can be a hard topic to study, both now and in the historical record, partly because there is not a set definition of who “counts” as homeless. It can can also be difficult to find first-hand narratives from people who have experienced homelessness. But it's clear that homelessness in Oakland didn’t end with the dissolution of Pipe City or the end of the Great Depression. If you’re interested in learning more about homelessness in Oakland throughout the years, and especially about how it was covered in the media, the vertical files are a great place to start. The version of history you'll find in these files is never the complete story - it depends on what was published as well as what librarians of the time thought was worth clipping and saving. But we have folders on homelessness, housing, cooperatives, and hundreds of other topics available for you to examine. If you're like me, no matter which topic you choose, you'll be fascinated to see how the discussion of the same issue has changed over the years.

Add a comment to: Pipe City and the Vertical Files