Founded in 1962, the Afro-American Association taught African Americans history, race pride, and self-reliance, and had a significant influence on the founders of the Black Panther Party.

Of all the topics people come to the Oakland History Center to research, few subjects are more popular than the Black Panther Party. If Oakland has contributed anything to society that is internationally known, it’s the Black Panthers. So many books, articles, dissertations and films have been written about them, and deservedly so. But the Panthers did not spring--as many researchers assume--wholesale from the earth, without influences, mentors or predecessors. Taking them out of their historical context may not reduce their luster, but it certainly compromises the story of Black liberation struggles in America. One of the Panther’s key influences was a local organization called the Afro-American Association (AAA).

Founded in 1962 by a group of graduate and law students at UC Berkeley, the Afro-American Association’s central mission was to educate African Americans about their history. The founding members--Donald Warden, Donald Hopkins, Otho Green, and Henry Ramsey--knew that many of the obstacles that faced their community were due to lack of self-knowledge. They were inspired by the revolutionary rhetoric of Malcolm X and Robert L. Williams, the recent anti-colonial victories throughout Africa, and the enduring Black consciousness espoused by intellects like Dr. W.E.B. DuBois. People could not combat oppressive and discriminatory systems, the association’s leadership reasoned, without a belief that they deserved better than the conditions under which they lived. The group’s chairman was Donald Warden, a Phi Beta Kappa Boalt Law School graduate, who believed that until African Americans knew their history, they would forever fall victim to institutional racism, discrimination, and low self-esteem.

Teaching African and African American history was not a common or popular practice in academic settings in the early 1960s, so AAA members met people where they were: on the streets and on the Grove Street campus of Oakland Junior College (later Merritt College). Warden was an intelligent and charismatic speaker, drawing young people to him like moths to a campfire with his talk of Black empowerment and a rich African heritage of which they knew nothing about.

Teaching African and African American history was not a common or popular practice in academic settings in the early 1960s, so AAA members met people where they were: on the streets and on the Grove Street campus of Oakland Junior College (later Merritt College). Warden was an intelligent and charismatic speaker, drawing young people to him like moths to a campfire with his talk of Black empowerment and a rich African heritage of which they knew nothing about.

At the time Black people in Oakland were finding it hard to find work due to widespread job discrimination. The post-World War II prosperity that helped fueled the Baby Boom had not trickled down to communities of color. Those who managed to make it to college were often discouraged by professors and school counselors from pursuing higher education and professional careers. To respond to these conditions, AAA members held campus rallies, weekly Monday night lectures and populE Friday night community forums. By spring 1962 the group, reported to have 150 members, shared with the community the works of Black intellectuals, stressed the importance of research in political debate, and demonstrated how important education is to one’s self-esteem. Young people who had not found any representation during their high school years were introduced to new concepts like colonialism, the negritude movement, Marxism, and Black nationalism. AAA staged a demonstration in September 1963 at McClymonds High Schools to encourage students to stay in school, study hard, and excel. While the organization did not oppose the civil rights movement, the members felt that AAA's goals--empowering the community with education and economic empowerment, not necessarily integration--were more germane to Black advancement.

The group led various social and political campaigns including one that called for the relocation of one million Blacks out of the South to escape the virulent racism that people faced there. Warden was quoted in the Oakland Tribune as saying:

“Conditions in the South can no longer be tolerated. It’s better to live in tents in the Bay Area than to live in tents and be lynched in the South.”

Warden sought financial support for this plan from Blacks in the North, civil rights groups, and state and government agencies. Members of the group also became involved in community organizing, local school curriculum debates, and political actions like boycotts of stores that practiced discriminatory hiring. They advocated for the hiring of Blacks in various industries including broadcast journalism. They picketed KQED public television station, demanding more Blacks as on-air talent and behind the scenes. The group also produced a Sunday afternoon radio show, featuring Warden as host on KDIA. When Oakland hosted the CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) National Convention in July 1967, whose theme was "Black Power: the Blueprint for Survival," the Afro-American Association represented local concerns.

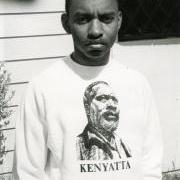

The Afro-American Association’s impact was quickly felt, especially among younger African Americans. Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, were among the young people who attended the association’s forums and lectures. The men would go on to co-found the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in October 1966. One of the association’s members--Kenny Freeman--penned the Panther’s legendary 10-Point Plan. Member Ron Everett (later Ron Karenga) went on to found the cultural practice of Kwanzaa through his Los Angeles-based US organization. Disseminating information about the African American experience not only instilled race pride, it fueled ambition and refocused people’s cultural aesthetics away from white models of beauty and artistic expression. Both the Black Power and Black Arts movements of the 1960s and 1970s were influenced by the association's efforts to center Black achievement, aesthetics, and political consciousness.

By the fall of 1963, the association was reported to have 5,000 members nationwide.

The association’s influence was widely felt not just by the members of the Black Panthers but by community members who went on to enter politics and the judiciary, people like former Oakland mayor and Congressman Ronald V. Dellums and United States District Judge Thelton Henderson.

On April 23, 2007, East Bay Congresswoman Barbara Lee (D-13th) honored the Afro-American Association before the California State Assembly on the 45th anniversary of the organization’s founding.

To learn more about the Afro-American Association and the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, check out these electronic resources:

Living for the City: Migration, education, and the rise of the black panther party in Oakland, California / Donna Jean Murch

Fanon For Beginners / Deborah Baker Wyrick

Stokely Speaks : From Black Power to Pan-Africanism / Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture)

Mainstreaming Black Power/Tom Adam Davies

Black Revolution on Campus/ Martha Biondi

The Black power mixtape 1967-1975: a documentary in 9 chapters / written and directed by Göran Hugo Olsson

Remaking black power: how black women transformed an era / Ashley D. Farmer

Add a comment to: The Afro-American Association: Forerunner to the Panthers