The African American Museum and Library at Oakland spotlights the archives of the Williams' Family as Black History Month 2021: The Black Family: Representation, Identity, and Diversity comes to a close.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History has designated the theme for Black History Month 2021 as The Black Family: Representation, Identity, and Diversity. The African American Museum and Library at Oakland has more than 160 collections documenting the histories of pioneering African American families in Oakland. AAMLO also has oral recorded histories that document the lives of both prominent and everyday families exploring the lives of history makers in Oakland. One such story that comes to you from the AAMLO archives is that of legendary Motown designer to the stars, Henry Delton Williams. Here is his life’s story.

The Williams’ family migrated to California around the mid-1940s from Louisiana. They came in search of a better. The Williams family, consisting of five members, was a part of the Great Migration where African Americans journeyed West in search of better opportunities, and escape from the challenges of Jim Crow, racism and tenant. Hearing of these opportunities, like many other African Americans the Williams’s found themselves in West Oakland. Henry Delton Williams father worked for the Oakland Naval Supply.

African Americans who migrated westward still faced challenges, including prejudice. This bias came not only from whites but also from Blacks. The relationship between African Americans already here, and those coming from the South wasn’t without challenges. The search for employment proved difficult as the lighter skinned blacks were able to find employment before the darker skinned blacks. This put African Americans that were fair skinned in a dilemma. As Williams put it, the lighter skinned blacks “suffered probably more because they weren’t accepted by the whites, nor the blacks.”

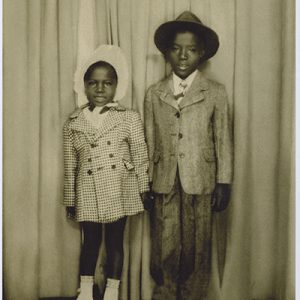

Family life was very important to the Williams’. His father worked, thereby allowing his mother to work at home to take care of the children. Their main priority was to provide basic comforts and raise their children. Henry, as the oldest of the siblings, was also responsible for looking out for his brothers and sisters while his parents were away from home. Seeing the work ethic of his father earning a living, Williams also wanted to earn income to buy the things that he wanted. He began working at the young age of seven gathering gallon jugs from neighbors in the new Harbor Homes community. The homes had no gas stoves. He would take the jugs and fill them up at the neighborhood coal oil store. With his entrepreneurial sense he earned 25 cents per jug. He later landed a paper route with the Oakland Tribune in the 7th Street neighborhood.

Library

Arriving in California brought the vision of a better life and opportunity for the Williams family. However, prejudicial treatment and also existed in the Bay Area, though not as blatant as in the South. Williams recounts how everyone knew “their place” in society and stuck to it. Living just blocks away from the Main Library (now home to the African American Museum and Library at Oakland), he would walk past the building afraid to come in. African Americans were allowed to come into the building but as Williams put it, you would be made to feel so uncomfortable coming to the establishment. This led many, like Williams to not patronize the branch. It’s ironic that the building that Williams did not feel like he was welcome in is now the home for his collection.

Education

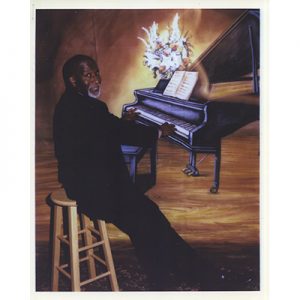

Williams studied at Laney College to become a designer tailor. After completing studies in design, fabric, and texture he began making clothes for himself and later for others. Williams made both slack suits for men and dresses for women. He used his creativity to change the look of how men and women would attire themselves. Seeing men wearing the basic gray and, black khakis, he began changing color schemes to create a new exciting wardrobe for them.

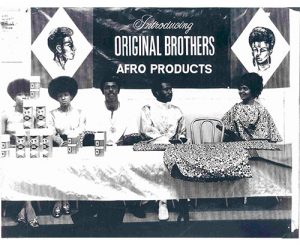

The Original Brothers

Williams’ shop, The Original Brothers, opened its doors at 1805 San Pablo Avenue in the 1960s. His first big contract was making slack suits for the Whispers. Success followed with him designing the church robes that the Hawkins singers wore when recording the gospel hit, Oh Happy Day, at the Oakland Auditorium.

One popular item designed by Williams was the dashiki. With the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the rise of the Black Panther Party and developing interest in African dashikis became the fashion statement of the times. The Original Brothers became known as the home for the dashiki. As the decade of the 1960s and days of dashiki wearing were nearing an end, The Original Brothers also began to wind down and a new chapter in Williams life began -- Hollywood.

Of course the seeds for Williams career path were planted in him as a small child. At the age of five, he dreamed of making it to Hollywood and perform in films. Just a couple of years later, Williams became “fascinated with the feel of the fabric” at the young age of seven. His father would always bring home textiles and he would watch his sister sew pieces of cloth together. Though Williams did not end up in Hollywood making movies he relocated to the city known for its moving images.

In a career that lasted nearly 50 years Williams has designed outfits for some of the most famous figures in Hollywood. Stars who wore designs created by Henry Delton Williams included Martha Reeves, Tina Turner, Freda Payne, Lenny Williams and more. As a costume designer, Williams created apparel for films such as Adios Amigo starring Fred Williamson and Richard Pryor.

For more information on Henry Delton Williams, please see the Henry Delton Williams Papers at the African American Museum and Library at Oakland’s page in the Online Archive of California.

Add a comment to: The Black Family: Representation, Identity and Diversity