A little bit about how the library uses the Dewey Decimal System to organize ALL HUMAN KNOWLEDGE!

If you've been to the library you know we have a LOT of books, and if you've been to the reference desk you know that we can usually guide you directly to the area for a topic you're interested in or to a specific book. This is possible not because librarians know everything, but because we know how to use the Dewey Decimal System.

The first thing to know about Dewey is that it uses numbers to represent subjects. Almost any subject you can think of has a corresponding Dewey number. We use Dewey to organize nonfiction materials at all of the Oakland Public Libraries. Other sections (like fiction, biography, and test prep) are arranged alphabetically.

Each book in the nonfiction section has its own Dewey call number, which makes it easy to find the area for a topic or to find a specific item. You can browse all the cookbooks or all the sheet music, but you can also go straight to the book you want.

Dewey numbers are formed one digit at a time, starting from the left.

The Ten Main Classes (the first digit) represent the most general subject areas:

- 000 Computer science, information & general works

- 100 Philosophy & psychology

- 200 Religion

- 300 Social sciences

- 400 Language

- 500 Science

- 600 Technology

- 700 Arts & recreation

- 800 Literature

- 900 History & geography

At the main library, asking for the area for religion, science, or history (or any of those other topics) is probably not going to be extremely helpful, since each of those classes fill up several long rows of bookshelves. If you go to the start of one of these sections you'll find general overviews of the subject - books that talk about “social sciences” in a very general way will be assigned the call number 300. You can also be sure that any call number starting with a 4 is going to be generally about language, no matter what the following numbers are.

Each of the 10 Main Classes is split into 10 more specific subjects, and these are called the Hundred Divisions. So, for example, let’s look at the 500 class: Science.

- 500 Science

- 510 Mathematics

- 520 Astronomy

- 530 Physics

- 540 Chemistry

- 550 Earth sciences & geology

- 560 Fossils & prehistoric life

- 570 Life sciences; biology

- 580 Plants (Botany)

- 590 Animals (Zoology)

In these call numbers, which are still pretty general subject areas, you’ll find overviews of books about chemistry or plants. If you want a book about a specific type of animal or about how earthquakes happen, you’ll need to get even more specific.

The third digit of each number is assigned with the Thousand Sections.

Let’s look at 590:

- 590 Animals (Zoology)

- 591 Specific topics in natural history

- 592 Invertebrates

- 593 Marine & seashore invertebrates

- 594 Mollusks & molluscoids

- 595 Arthropods

- 596 Chordates

- 597 Cold-blooded vertebrates; fishes

- 598 Birds

- 599 Mammals

If you’re looking for books on a specific type of animal a three-digit number is still not specific enough. That’s why we have numbers beyond the decimal point. The more numbers after the decimal, the more specific the topic that number represents.

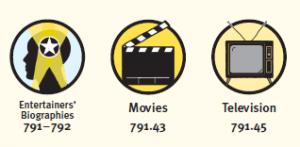

The numbers sometimes get quite long because popular things to read about today - current events, computers, movies - either hadn’t happened, hadn’t been invented, or just weren’t widely published about when Melvil Dewey invented this system in 1873. It’s also interesting to see where Dewey’s personal worldview is reflected throughout the system. Although Dewey was American, his system is definitely Euro-centric. When numbers are arranged by geography (as in the 910s - the travel section) books about Europe always come first, starting with Britain.

In the religion section, which takes up all of the 200s, “other religions” (non-Christian religions) are only allowed numbers 290-299 while topics about Christianity reside in numbers 230-289. This can lead to a lot of decimal places because there just isn’t enough variety in the first three digits to allow for books on many different topics on the many non-Christian religions or types of computer software that exist. Luckily, since we can add as many decimal points as we need to, we’re able to create new numbers to represent a much wider variety of topics.

In the religion section, which takes up all of the 200s, “other religions” (non-Christian religions) are only allowed numbers 290-299 while topics about Christianity reside in numbers 230-289. This can lead to a lot of decimal places because there just isn’t enough variety in the first three digits to allow for books on many different topics on the many non-Christian religions or types of computer software that exist. Luckily, since we can add as many decimal points as we need to, we’re able to create new numbers to represent a much wider variety of topics.

The cutter, or the non-number part of the call number, is there to help you find a book when there are several which have been assigned the exact same numbers because they're the exact same topic. This is usually the author’s name or a word from the title, but sometimes it can be a strange series of letters and numbers. If you’re looking for a specific book, it’s always a good idea to write down the entire call number - all of the numbers AND letters - because sometimes there are dozens of books (or more!) with identical call number digits. The number for books about actors and actresses (791.43028) includes almost 400 items at the Main Library alone, so without the cutter, you could get pretty lost trying to find the one you want.

If you’re looking for a specific book, it’s always a good idea to write down the entire call number - all of the numbers AND letters - because sometimes there are dozens of books (or more!) with identical call number digits. The number for books about actors and actresses (791.43028) includes almost 400 items at the Main Library alone, so without the cutter, you could get pretty lost trying to find the one you want.

I’ll write more about how to use the library catalog to find the book you want in the next installment of the Dewey blog, but remember that you can always ask at the reference desk if you need help finding anything. That's why we're here!

The images in this post are a few of the pictograms created by Oakland graphic design firm Shelby Designs & Illustrates, and funded by a 2003-04 LSTA grant from the State Library of California. You can see all 88 pictograms on posters and shelves throughout the library.

Add a comment to: Why do we need the Dewey Decimal system?