Here's a question for parents: What would you do to see that your child gets the best quality education? Would you remove your child from the school district they are in and put him/her into another? Would you take them and put them in private school, if you could afford it? Now, what if you were a parent not only paying taxes to fund the school your child went to, but also one at which they were not welcome? This was the dilemma that African American parents faced in their fight to integrate Oakland schools.

Welcome parents and students to the 2021-2022 school year. The 2020 school year was one we will not soon forget. From zoom classes, to the technological divide, to drive thru graduations, 2020 was one of the most challenging years we will live through in our lives. It has been a trying time for students throughout the country and the world to get an education while fighting a global pandemic. From in person instruction to online instruction, teachers have been the backbone for educating the leaders of tomorrow.

As students have begun another school year, the importance of an education should not be taken for granted. For many years, lawmakers denied African American students the right to an education. School segregation in California began as a custom, not law. To ensure that African American students received an education, members of the black community opened all-black private schools. Soon laws were created that would emphatically close the door to public education for students of color.

By the mid-1850s the first laws began to take shape to exclude African American and other minorities from attending public schools. For example, School Law of 1855 gave funding to schools depending on the amount of Caucasian students were enrolled. Just a few years later California school codes in 1860 officially led to segregation as African Americans, Asians, and Native Americans were banned from attending California public schools.

In 1854 the Grass Valley Common School began admitting African American students over the objections of some white parents. These parents brought their concerns to the school district. The district, however, continued to allow African American children to attend.

School districts such as Grass Valley were sympathetic to the plight of African American children wanting an education. However, the state superintendent threatened to take state funding for their district if integrated. If schools were caught breaking the law, districts risked having their state funding suspended.

Children of African or Mongolian descent and Indian children not living under the care of white people shall not be admitted into public schools except as provided in this act, provided that upon the written application of the parents or guardians of at least ten such children to any board of trustees or board of education a separate school shall be established for the education of such children and the education of a less number may be provided for in separate schools or in any other manner. The same laws rules and regulations which apply to schools for white school children shall apply to schools for colored children. [Section 5.7 – School Code]

Between 1852 and 1879 African American students received separate education. Years later the Revised School Law of 1866 gave districts the option to have separate schools. Black schools were established by law in order to allow students the opportunity to get the education. Due to the low enrollment numbers, many public leaders refused to create schools for African American students. The state initially provided funding to these schools, but after protest from white parents, state funding was pulled.

Black Schools (Brooklyn)

With laws preventing African Americans children from attending white schools, the responsibility of educating them fell on the African American community. One such educator was Elizabeth Thorn Scott. (see Dorothy Lazard’s post Elizabeth Scott Flood: Early Oakland Educator).

At the 1865 State Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California, attention turned to changing laws related to educating African American students. The focus centered on school districts that failed to establish schools for Black students when there were not enough students in that community. Another goal was to repeal the 1852 law that prevented African Americans children from attending public schools. Those attending the 1865 Convention were forward progressive thinkers.

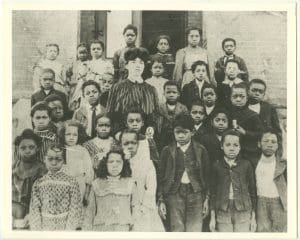

Separate schools were only established if there were more than 10 African American children in the surrounding neighborhoods. The Brooklyn Colored School, located at 1008 10th Avenue, opened in 1867 in the town of Brooklyn and served as the first public school for African Americans in Alameda County. Mary Sanderson served as its teacher from 1867 – 1871. In 1871 as families began to leave the community the minimum number of students fell below the required 10. Based on the law, it was forced to closed its doors.

With Brooklyn’s closure, students found themselves facing a number of obstacles. Those obstacles included not only state law prohibiting integration, but white parental objections. The thought of integration was not received well by parents of children in white schools.

Integration

With the California legislature not taking action, combined with the closure of Brooklyn schools, parents needed to act. African American parents took their plight to the Oakland school board. After much debate the school board went against the State School code. In a 5-2 vote in 1872 approved integrating the Oakland school system.

African American Educators

Though the fight to integrate schools was now over, the next battle would come decades later in the form of representation – teachers that looked like them. Ida Jackson waged a fight for years to become the first teacher in the Oakland Public Schools system. In 1926, Jackson was hired as a long term substitute teacher at Prescott School, making her Oakland’s first African American school teacher.

The AAMLO Archives has a number of collections on the first African American school teachers in a number of Bay Area cities, including Ruth Acty for Berkeley Unified School District and Gladys Jordan for Emeryville Unified School District.

You can also read a previous blog post on Oakland Public School’s first African American school teacher, Mrs. Ida Jackson.

As students of Oakland make their way back to the classrooms, please continue to wear a mask to protect yourself, teachers and fellow classmates.

Add a comment to: When Can I Learn? African Americans Begin School In Oakland, California